Towards an intellectualisation of the fashion industry: rethinking its role into the social structure

For a long time devalued, the role of fashion into our structure is a real social and philosophical question. It is not before entering the industrial area, in which fashion as a subject, was analysed through a sociological lens by searchers such as Gabriel Tarde or Georg Simmel. These theories tend to place fashion as a tool to decipher social mechanisms like imitation or distinction. Although their work truly helps understanding the deep implications of fashion, the latter still had a hard time to be taken seriously within the society. Clichés on its frivolity and superficiality are still very vivid and we cannot blame the audience for having such perceptions – since they are the most mediatised aspects. However, when we decide to go further and go above the mainstream representations, fashion has a fundamental role in cultural transformations. More than simple trends and garments, could we claim this industry is about questioning the establishment and asking the ‘real questions’? Should the role of fashion be to reflect more the actual collective concerns?

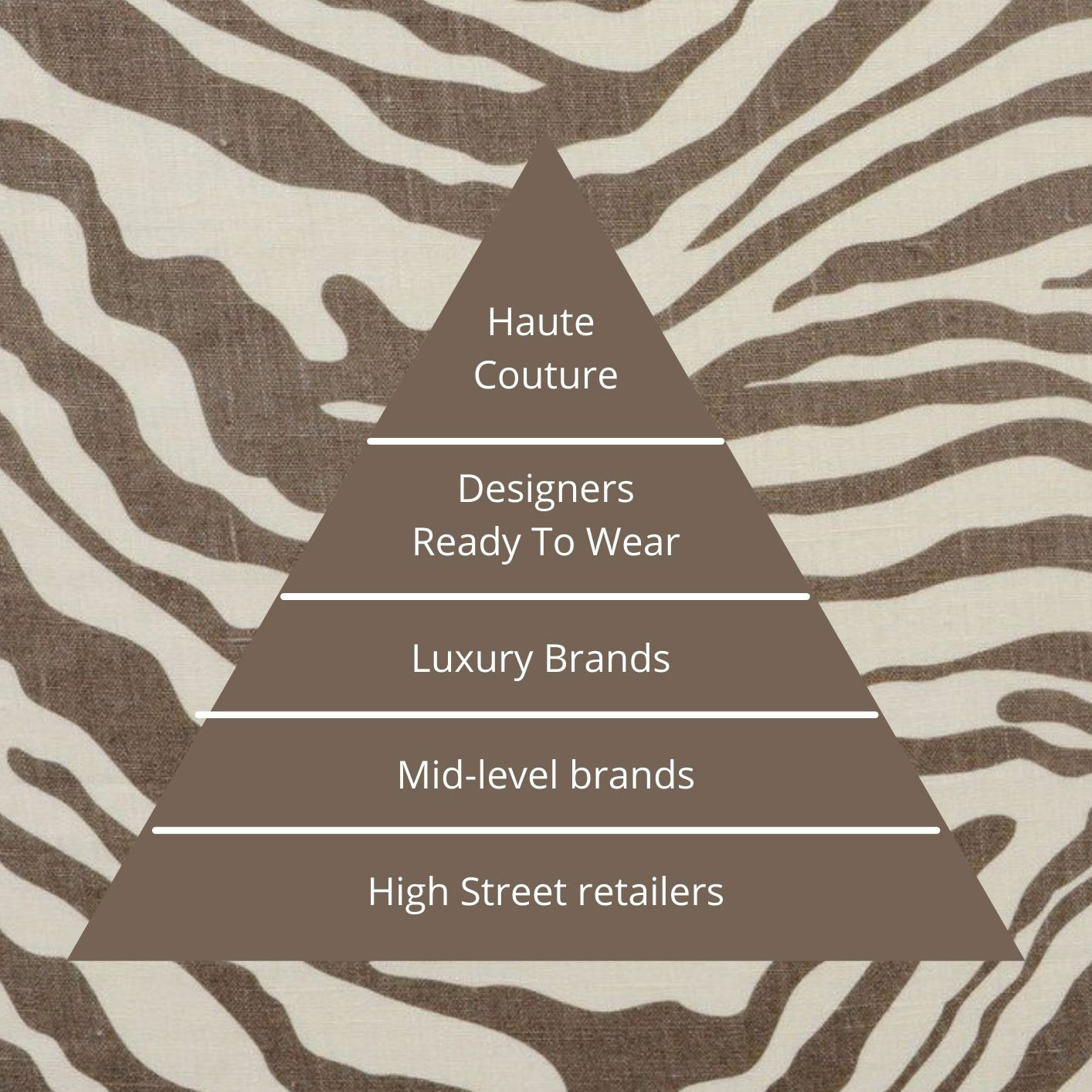

At first, truly bounded to social class, fashion was considered as pointless and was truly gendered. It was the matter of sociable women. Far from political or intellectual activities, it was put aside the academic and intellectual field. Although Voltaire, Mandeville and Platon wrote about fashion, their visions were often associated to luxury. We need to wait until the 19th century to see relevant theories emerging on the role of fashion and its influence into the social structure. A lot of writings from these periods were a solid assistance in understanding the shape and functioning of this system. Searchers such as George Simmel had formulated a theory based on a pyramid able to explain how trends spread within social classes in the western society. American anthropologist Alfred Kroeber analysed fashion as a tool that leads to transformations. These studies are conditioned by the epoch they were created in, hence, they could appear as irrelevant facing the actual realities. However, their critique gives an important base to analyse the actual industry. Indeed, it is because of the past conceptions and practices that some actors nowadays are committed to dismantle this common psyche placing fashion as a superficial object out of the social life. Through history, we can see that garments were a matter of social class and aspirations to belong to a certain community as theorised by Simmel. As the society itself, the system was based on a pyramid – at the top were the wealthy groups and below the popular ones. With time, as we were going to a more individualistic and fragmented social dynamic, this model was slowly but surely appearing obsolete. Nevertheless, the imaginary related to luxury and exclusivity was still growing and was well settled.

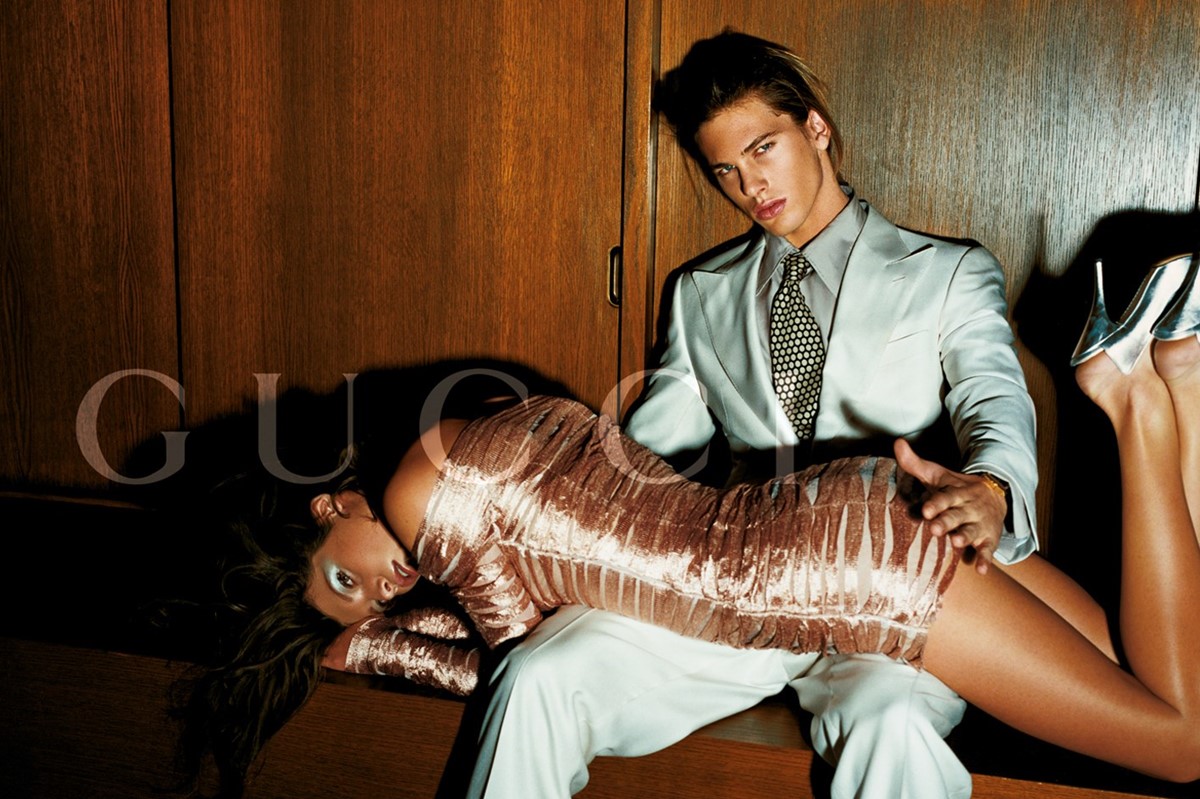

The peak of this approach is occurring during the 2000s. It is at this time that we have the most showy and theatrical version. Fashion labels were displaying an image based on distinction. The iconography associated to this period reveals an aesthetic bound to notion such as luxurious, thinnest and shiniest. It goes even further with Tom Ford controversy campaign for Gucci in 2003 shot by Mario Testino. We could argue that this editorial on feminine servitude will not be interpreted and welcomed the same way in a context of increasing gender equity claims. These past representations are now very far from the current social preoccupations. During the first decade of 2000s mass consumption and over production were abusive practices not necessarily pointed out by medias. Although some sub-groups were concerned by the damages brought by capitalism, the mainstream psyche was embracing this ideology without questioning the social and environmental consequences it had. It is not until the 2008 crisis that individuals had to face the flaws of such organisation and its impact on human lives. The current health emergency has added even more consistency to irregularities we had implemented by pursuing a harmful model prioritising profits over individuals. The 2008 economic crisis is still having impacts on today’s aspirations. It has deeply shifted perceptions on consumption. Today, a conscious vision has appeared. More than a meaningless and simple act, buying has become a statement for consumers. Through it, they can define their-selves. This translates into a desire for actors to put fashion within the social life as a tool able to educate in order to embrace improvements and awareness. Nowadays, Individuals want the role of fashion to be more appropriate to their own realities and commitments. For fashion labels, it means that it is more about building a relationship than selling a product without any consideration for the actual state of our society. Although some well-established brands are maintaining this imaginary full of exclusivity and superficiality, they are also struggling to be heard in some fashion communities where statements matter.

Looking at emerging actors within the fashion industry makes us truly comprehend the process of intellectualisation that is currently occurring in the field. Less attached to the traditional system, they are not afraid of going outside the pre-established norms by bringing depth and purpose to the act of creating garments. The meanings of their work come from various sources such as their own environment. That is what inspired the young designer Tara Mabiala based in Switzerland. While she is still studying how to practice fashion according to her own terms, Tara already has a pretty good idea of the role and power of fashion in our social structure. Although she started by learning architecture, the fashion discipline was her final choice. At the Haute Ecole d’Art et de Design, she explored the idea of “being conscious of the social, economic, cultural, historical implications of fashion”. To her, there is definitely a work to do when it comes to the place and representation of this field. While searching about design online, the resources show us everything from car engineering to product design. However, “fashion is very rarely included as it is mainly seen as superficial and frivolous as you mentioned before. When, in my opinion, there is one thing common to a vast majority of the population from different social and cultural backgrounds: body coverage – meaning clothes.”

|

|

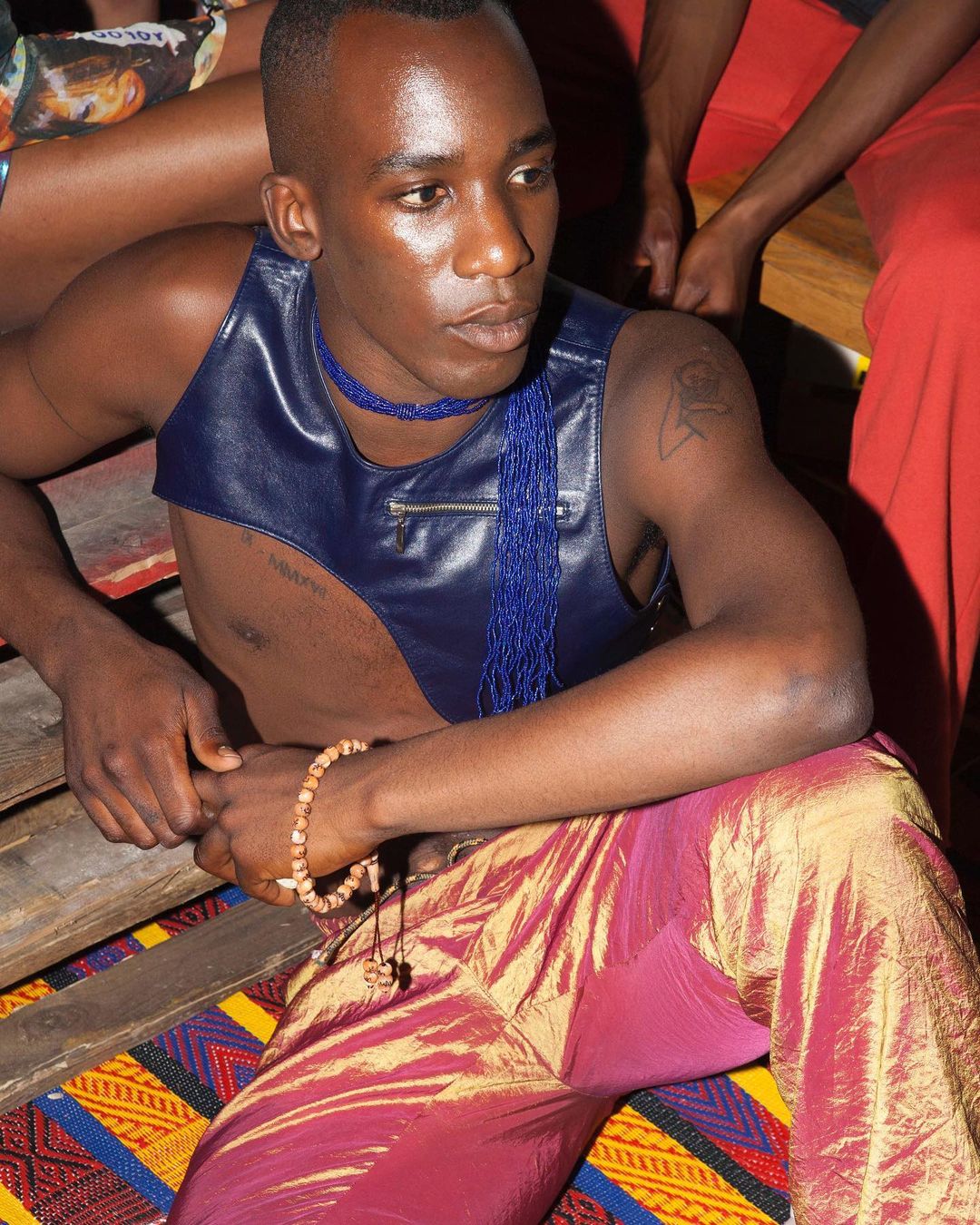

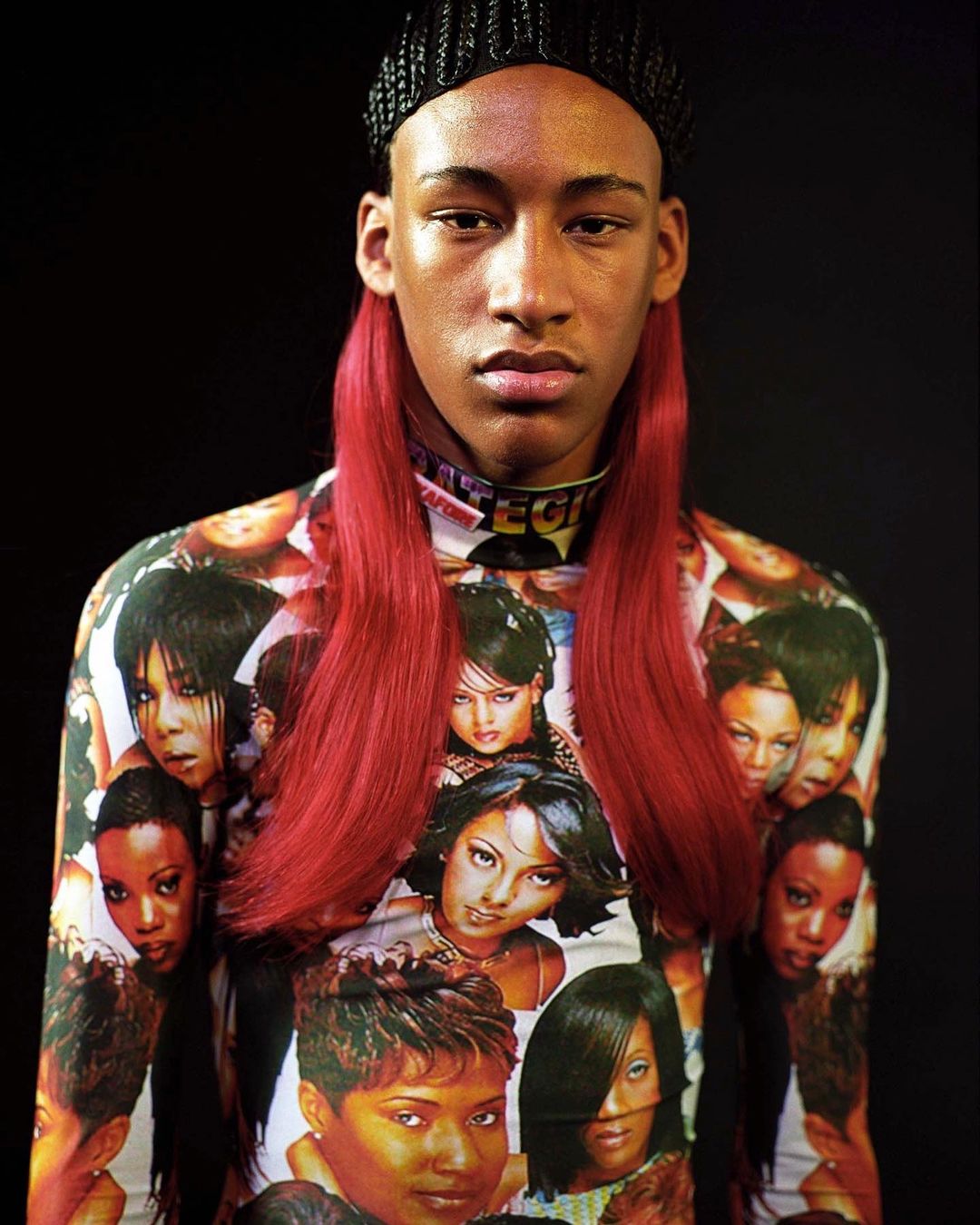

Tara Mabiala – Article 15, photos by Elsa Guillet

To challenge the lack of legitimacy society gives to fashion, Tara turns her attention on the sense of collectivism and her own environment. Tara’s work is driven by her personal interests: the rituals and symbolism of garments in African communities. Additionally, she is using a macro approach as clothing leads to specific social dynamics. In her Article 15 collection, Tara was inspired by how Congolese are using clothes in everyday life. Article 15 is often used by ‘sapeurs’. It refers to the most known and none written article of the Zaire Constitution. “My BA collection, Article 15, is directly inspired by personal experiences, things I’ve seen and stories I’ve imagined about clothing in Congo. My father being from Democratic Republic of the Congo I often travel there. I have spent a lot of time observing the way my aunts and uncles, street children, sapeurs and even sorcerers would make a piece of clothing their own” she describes. From accumulation to layering, the goal of this collection is to highlight the mystical and ostentatious sphere of fashion in this culture. “I did a lot of research using second hand clothing, my own favourite pieces or even some clothes from my family” explains Tara. Article 15 is an ode to her heritage through clothes free of class and gender restrictions. Her last collection – When She left the Room the Spirits Went with Her – celebrates her legacy in a different way. Festive clothing are used to explore the relationship of Afro communities to traditions. Juxtaposed this aspect, Tara pays tribute to the Blaxploitation movement which aimed to place Afro character at the centre of the piece.

As a designer, Tara feels she has to commit and express it through her practice. With Afro-descendant origins, “Being myself already allows me to challenge social norms – especially when growing in the western society”. Very proud of this legacy, she is using her mixed heritage to reflect on her own abilities, opportunities and the complexity of her position. Hence, those aspects are deeply influencing the way she perceives the role of a designer. The chase of economic growth in the fashion field, prevents designers from potential positive impacts they could have on the inside. Indeed, according to Tara, the quest of profits tends to put designers on an irrelevant and unjustified pedestal. “I would love to see fashion designers get more involved in cultural and social matters. The educational background we have given through our studies should allow us to think and express these issues in a way that benefit the society itself” she claims. She certainly has a critical point of view about the industry, nevertheless aesthetic plays an important part in her process. The latter can be a tool used by sub-groups as a way to embrace their differences from the majority. On this aspect, Tara refers to a specific quote from bell hooks’ book Art on my Mind “It is important, when we look at the work of any group of people who’ve been marginalized, whether we are talking about white immigrants or any of us, that there be a willingness to acknowledge complexity – profundity – multi-layered possibility” This self-awareness is what federate a community while facing oppression from the mainstream norms. Applied to fashion, it leads to Didier Eribon’s concept of “aesthetic of existence”. It is the act of reformulating or recreating “one’s own life, and the conditions in which it can take place: making it more liveable.” For Tara, this notion is definitely verbalised through clothes. She gives the example of Queer community that used garments and styling as a way to draw their own narrative. Tara thinks it is where lays the real role of a designer. They need to speak for the community they are part of, thus representing themselves.

|

|

Tara Mabiala – When She left the Room the Spirits Went with Her, Shot by James Bantone

Racial questions are not the only issues the fashion industry can address to their audience. Ellis Jazz, London-based designer- is working more on redefining body standards and the notion of erotic. After graduating from the Royal College of Art in 2019, she had the chance to present her collection at the digital London Fashion Week in September 2020. Her hand made knitwear items represent a laborious work aimed to create designs that are like loving gifts. What is automatically striking with Ellis’ imaginary is the fact that it is going against the traditional norms of body shapes and sensuality. While in 2009, the late Karl Lagerfeld was saying that no one wants to see curvy women on the catwalk, Ellis is today convinced that there is a demand and market for all types of bodies. “There is a need for clothing that fits all different kinds of bodies, a need for a variety of people to be represented in advertising, lookbook and editorial imagery” she confirms. The necessity for diversity in terms of body shapes is not new, and it is much needed in the luxury segment. Ellis thinks “it is insane that is taken until recent times to address this. “ It is well-known the western fashion industry has imposed specific body types to promote and fulfil in shows and editorials. Most of the time unrealistic and unreachable, these standards have done a lot of harm to women’s representations.

|

|

Ellis Jazz – Doves a Tender Drip of the Finest Saccharine Sanguinary, Photos by Scarlett Casciello

Above these visions, restricting body shapes is also an inconvenience in terms of possibilities in fashion design. Indeed, Ellis is convinced that “working with models who are a variety of sizes and shapes offers up such great opportunities for designers to fully explore the possibilities of clothing. It just seems senseless to narrow down the types of bodies you would want to represent your clothes.” The consequences of such approach are unworthy since it cuts designers off from exploring different beauty and stunning ways to play with lines. It is not about making diversity a gimmick but more about embracing the fact that we are more than our bodies. Diktats are not including all the intangible features that make a woman sensual or desirable. According to Ellis, confidence – a central component in her work – is more relevant to explore while designing. Physical attributes are totally subjective, therefore it should not determine the attractiveness of a woman. On the contrary, personality traits should prevail.” I am inspired by women who are seductive by way of self-esteem, self-awareness and strength being a source of attraction. A sense of ownership of one’s own image is such a powerful thing” says Ellis.

|

|

Ellis Jazz – Doves a Tender Drip of the Finest Saccharine Sanguinary, Photo by Scarlett Casciello

She has a true love for women looking strong and ‘sturdy’ in fashion visuals. “Perhaps this is a reaction to the types of fashion imagery I grew up with, the resurgence of the waif look in the 2008 era happened just as I was deciding that working in fashion was where I wanted to spend my career and was applying for fashion school” she explains. Appearing unhealthy has been the norms for a long time and it still is for some designers such as Heidi Slimane that are glorifying thinness. Far from these values, Ellis is part of a community of designers who want to reposition notion such as eroticism and sensuality. “Quite often designers can just be translating societal conversation into something tangible,” thus her role – as a knitwear designer – is to normalise diversity in terms of body shapes in fashion imagery and creation. To establish such values, Ellis is convinced that it has to happen in a collective way. This process of acceptance is aimed to be realistic and to inspire the next generations in having a broader representation of body shapes.

|

|

Ellis Jazz – Doves a Tender Drip of the Finest Saccharine Sanguinary, Photo by Scarlett Casciello

In this process of intellectualisation, our last object of study is the brand Wekafore created by designer Wekaforé Maniu Jibril. Born in Nigeria, his first memories of fashion are related to his mother’s textile factory-workshop right outside their family home. Most of his childhood was marked by the work he was doing for her. It is certainly a nice way to first get introduced to fashion. Most of all, it allowed Jibril to go even deeper in his conception of fashion design while growing and maturing his visions. Now settled in Barcelona, he is – additionally to his label – the founder of the Voodoo Children’s Club. This community aims to celebrate contemporary Afro-aesthetic and aspires to build the narrative of the future. When analysing the work of Jibril, it is essential to be aware of the fact that Africa gathers a lot of communities and cultures that cannot be put under one label. The research and inspirations he uses to create his designs are referring to specific societies and historical eras. “Africa is very big, there are so many realities existing at the same time – the western psyche couldn’t possible envision its entirety” he explains. Without fully grasping the heteroclite aspect this continent has, it is hard to envision and understand its beauty and complexity. The label Wekafore is an ode to the past, present and future of Afro-communities. From Malick Sidibé‘s work to Fela Kuti, it is the roots of these cultures that inspire Jibril as a designer.

|

|

Wekafore, photos by Viridiana Morandini

At the centre of Jibril’s approach lays a desire to celebrate forgotten eras in Lagos and other West African cities after colonisation. More broadly, his work addresses the question of Negritude that he defines as “a derivative of the word Negro or the phenomenon of being ‘negro’ black or of African descent. It’s the state of blackness, it’s the state of being black, and it’s the thread that connects every human that is a derivative of the continent.” His blackness deeply drives his creative process. In his design Jibril is translating what he knows best: his legacy and his city (Lagos). Truly aware of the fact the fashion experience is not the same in the Western cultures than in Afro societies such as Nigeria, he is convinced that we cannot use the same tools to analyse both universes. Instead of comparing, we need to look at Afro-aesthetic as an individual subject that gathers plenty of sub-genres. It is where the notion of Negritude is crucial. Initially used as a framework of critique and literary theories, this concept was aimed to cultivate “Black-consciousness” across the continent and its diaspora. Founded by Aimé Césaire in the 1930s, it stands against colonisation and embraces a Pan-Africanism approach. The DNA of the notion is visible through the label Wekafore. Jibril’s version of Negritude is certainly more in the zeitgeist, nevertheless he doesn’t cut off with the origins of such movement. Through his practice, he wants to avoid the “the dehumanisation of the African continent.” Hence education and communication are the only factors that allow the situation to evolve.

|

|

Wekafore, photos by Viridiana Morandini

In the quest of sharing truthful knowledge and instruct, fashion has fundamentally a role to play according to Jibril. “In my perspective fashion is a great communication tool, but just as every other powerful tool known to man – people have used it for destruction and chaos, these are codes and symbols and shapes” he explains. That being said, for the designer, since its form and purpose are evolving through time, it gives an opportunity to the actors of the industry to shape it according to the emerging social needs and aspirations. Going further, he thinks all creative activities are a way to celebrate Afro-culture according to the vision of insiders. Therefore he is also investigating the music industry as a medium able to honour the past and also the future of African communities. With the Voodoo Children’s Club, before the pandemic, he was organising what he likes to call “curated contemporary African rave experience”. From afro-punk to disco, these events are a throwback to the culture of parties in post-colonial societies. As a multi-disciplinary designer, Jibril is exploring various mediums to give his own version of Afro experiences. Challenging notion such as black masculinity or negritude, his goal is going above the simple act of creating and selling clothes. He managed through Wekafore to build a strong community, proud of this multi-layered legacies. Jibril is a designer that puts intellect and research in his approach – convinced that it has a crucial place in social transformations.

|

|

Wekafore, photos by Viridiana Morandini

This essay has explored the idea of using social, cultural or political claims in the act of creating garments that have purpose and meaning in opposition to the traditional and mainstream perceptions of fashion. Through the experiences of three emerging designers from different backgrounds, the goal was to highlight the influence their own environment has on the causes they address through their collections. From Tara, we understand that garments have a collective sphere and give a framework to understand a culture and its traditions. Ellis’ commitment to diversify body representations in the industry led us to question the opportunities such inclusive approach can give to fashion design. Finally, through Wekafore, we explored the notion of Negritude and the way it can apply to fashion – as a tool to educate on Afro-heritage and celebrate it. All these stories have the capacity to bring awareness on the power and role of fashion in the social organisation. At the heart of social changes, it has the ability to verbalise present and emerging aspirations. Although it is appearing clear social and environmental preoccupations have taken the fashion industry, we – the audience and actors – have to be aware of the use of such causes to generate more money. After all, we are still driven by capitalism and every causes that gather a lot of individuals can be used to create profits. If the intellectualisation process of the fashion industry is aimed to build a better and more sustainable system for the future, we need to get rid of the burden that is ‘woke-washing’. This time we cannot be content with tokenistic practices. We need to search for consistency and authenticity like in the work of Tara, Ellis and Jibril.